Published: 2021/05/06

Last updated: 2021/05/06

Several years ago, I came across an interesting series of posts talking about the concept of “depth” in Doom. A recent IRC conversation about the evolution of idtech engines and their competitors, and discussion of the subsequent gameplay and design changes, brought it back to mind. I decided that I’d like to make my own attempt at explaining just what it is that makes Doom so deep, even 28 years later, while its contemporaries lay relatively (though by no means absolutely!) forgotten.

First off, what am I meaning when I say “depth”?

Anon described it well – “the amount of possible different and meaningful choices the player is required to make during gameplay” (emphasis mine).

Why do I emphasise the distinction on “meaningful”? To exclude silly ideas such as “having 300 re-skinned weapons is much more deep than Doom’s 9”.

Secondly, what am I meaning when I say “Doom”?

Specifically, I’m going to focus on the gameplay and engine as originally used in The Ultimate Doom and Doom II: Hell On Earth, ignoring later games in the series, source ports, adaptations, and user-created content.

Let’s start from the ground up with the player character himself, the Doomguy. What about his character provides gameplay depth?

A cursory examination suggests nothing spectacular – like any FPS protagonist, he is able to move in essentially eight directions, pick up items, and fire weapons. Each of these seemingly simple elements, however, offer a lot of possibilities.

Doom is described as a “fast-paced” game. Why is that? It’s largely because Doomguy rarely stops moving for very long, but also because of his intrinsic agility, which is what provides the relevant depth.

This speed alone is a potent defence, both within the game world and relative to other typical protagonists, transforming the decision of whether to run from a simple convenience to a powerful tactical choice. That is to say, instead of merely acting as a fast-forward button when revisiting cleared areas, or providing a minor boost when navigating to another cover spot, it becomes a form of enhanced exploration, offence, and defence.

Exploration is aided not just by being able to investigate quicker, but also by enabling a limited form of jumping; the player is actually able to “glide” a surprising distance by getting a running start. While other protagonists might solve a navigation puzzle by jumping from pillar to pillar, Doomguy can actually accomplish the same by simply running fast enough.

Offence and defence are both aided via the usage of circle-strafing, the art of literally running circles around your opponents. While this can be possible to an extent in other games, few are able to do it with the sheer efficacy of the Doomguy, owing to both tight controls and his exceptional speed. This can take an otherwise unwinnable situation and make it entirely viable, both by increasing the ability to dodge projectiles while still dealing consistent damage and by tricking enemies into shooting each other, triggering infighting.

Naturally, all that speed also lends itself to another tactic: running away. While often undervalued, it is nonetheless a valid strategy.

Ignoring weapons and ammo, items in most FPS games tend to come down to health and shield refills. Doom, on the other hand, has, with some cross-overs:

There’s quite a bit to unpack there in this discussion on depth, so let’s examine the strategic choices offered in each category:

The primary challenge here is figuring out how to utilise the pickups efficiently, given that there is no sub-division of “unused” amounts. For instance, using only part of a medikit’s healing capacity doesn’t turn it into a stimpack or in any other way keep track of how much was used – any unused amount is simply wasted. This forces the player to strategise and to incorporate the location and types of available health into his overall plan.

Coupled with the fact that nothing in the game makes health spawn spontaneously, this leaves the map-maker in near-total control of how much health the player is allowed to regain. Players in varying degrees of health will be more likely to act with differing and correlated degrees of recklessness, drastically altering the playstyle and progression, which the map designer can then take further advantage of, for instance by leaving open the possibility of traps in seemingly-cleared health-rich areas.

Armour in Doom works a little differently than might be expected. Essentially, it comes in two classes, which I’ve termed “green” and “blue” for simplicity.

“Green” class is the default class until directly overridden by picking up blue combat armour or a megasphere. At that point, you remain in the “blue” class until directly overridden by picking up green security armour. Armour bonuses (the glowing helmets) add 1% to your armour points but do not change your armour class, even if your armour points dip below 100, or even to 0.

The difference between the two simply comes down to how much damage is absorbed: “green” class armour reduces damage by 33%, and “blue” class armour reduces damage by 50%.

Where, then, is the depth? It comes with the details – the simple fact that the damage reduction occurs by degrading your armour points by the same amount as the blocked damage. This has the net effect of making “blue” class armour degrade noticeably quicker. Additionally, green security armour cannot be picked up unless your armour points dip below 100%. These two facts can make green security armour both a strategic choice (it’s better to have some armour than to rapidly lose all of it to heavy enemy fire) and an obstacle (the player may want to try to avoid the armour due to desiring the higher protection).

The computer area map tends to completely transform the player’s strategy, as it usually shows, or gives strong hints towards, the location of secret areas, greatly increasing the player’s known available options.

Light amplification goggles can greatly influence the difficulty of a given area, especially because they make the partially-invisible spectres blatantly apparent (alongside all other enemies, of course). Their time-limited nature also means the player may need to decide when and where they are going to be most useful.

That same sentiment also applies to the radiation suit, but even moreso. While the goggles are a nice convenience, the suits are sometimes entirely mandatory to fully explore a given area due to the highly-damaging nature of the acid floors.

Berserk kits are interesting, not only for the same reasons as the other health items, but also because they can represent a sizeable offensive boost, especially for players with good footwork, as each punch hits like a rocket (sans splash damage). However, because they also grant a very powerful chunk of healing, players need to weigh their options between “emergency healing” and “massive power”.

Backpacks, at first glance, don’t seem like they affect player agency much – they just double the ammo you can carry. However simple they may be mechanically, that boost is very significant, and can drastically affect a player’s playstyle in regard to weapon favouritism. A super shotgun is much more appealing when you can fire it 50 times in a row instead of merely 25, for instance. The depth it provides is therefore indirect, but still significant.

Invisibility is particularly interesting, as experienced players know it to be a very double-edged sword. While it does make it harder for enemies to notice you, an enemy in normal conditions has a very predictable firing pattern once engaged. An enemy that has no real idea where you are fires randomly, which can make it very difficult to reliably dodge.

Invincibility is a little deceptively simple – it’s straight-up immortality, yes, but immortality can open up strategies that aren’t normally possible. For instance, a player might use it to antagonise enemies into infighting with zero fear of reprisal, or take advantage of the fact that splash damage from rockets is incredible at clearing out tight crowds of powerful enemies, especially when neither they nor your rockets can hurt you. One map in episode 3 even makes it nearly mandatory to use it to execute a “rocket jump” in order to find the final secret.

Doom’s weaponry is very well thought-out, covering a variety of use-cases without ever entirely deprecating a weapon, with the arguable exception of the pistol, which is at least useful for economically activating remote switches. Compared to its immediate chronological predecessor, Wolfenstein 3-D, where every found weapon was a direct upgrade of the previous, that’s quite a feat.

Unlike many modern shooters, which arbitrarily limit the player to 2-4 weapons in the name of “realism”, Doom II has a complete arsenal of 9 different weapons sharing a pool of 4 different ammo types (bullets, shells, rockets, cells). This spread of ammo and weaponry allows for a number of ways to engage the player, and makes the question of which weapon is optimal for a given situation much more open.

For instance, it’s often an open question whether or not to go for the sheer stopping-power of a super shotgun or rocket launcher or the more defensive/disrupting abilities of the chaingun or even chainsaw. While the former two weapons are much more powerful per-hit, they both have disadvantages – the super shotgun has a lengthy reloading animation after each hit (during which one is fully unable to counter-attack), and the rocket launcher has a very real danger of accidental suicide via splash-damage (as well as a more limited ammo pool in practice). On the other hand, while the chaingun and chainsaw are lacking in raw offensive capability, their extremely rapid hits have a very high chance of disrupting enemy attacks and movement, which can be highly valuable; they also don’t require reloading or have any lag between stopping and resuming fire.

Everything, in short, is balanced to some degree. Even the more powerful per-hit plasma rifle and BFG 9000 have caveats. In the case of the plasma rifle, the bright, noisy projectiles can make it difficult to process one’s surrounding environment, can miss due to being actual projectiles, and the rifle itself requires a moment of cooldown after firing any amount of shots. The BFG, while unequivocally having immense power, is also very expensive to fire (40 cells per shot), has an initial delay when firing, and has a very unique staggered firing sequence1 that takes practice to maximise the potential of; it’s also easy to waste shots in a crowd when trying to take down a single target.

There is a ton to be learned from studying Doom’s level design. For our purposes, however, let’s consider them purely from the perspective of depth.

One thing to note in general is that map size does not intrinsically correlate with depth – it depends on the design of the level. Things such as enemy and obstacle placement and the flow of the map are what matters. If a map is large and empty, true, your PC can occupy more potential coordinates than a smaller room, but if it doesn’t change or influence anything, that size is wasted.

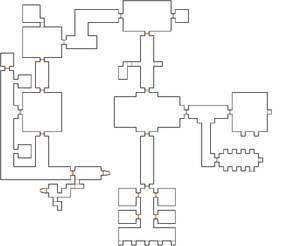

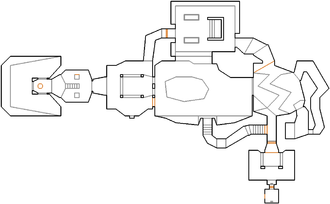

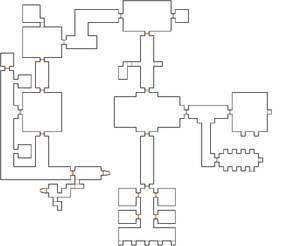

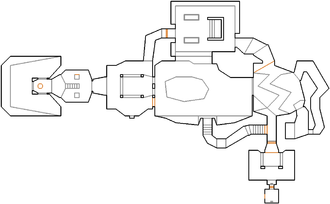

With Doom, you don’t see that. Instead, you have levels where every element is carefully constructed to allow for a variety of approaches on the player’s part while still maintaining the action and holding the player’s interest. Enemy, item, and obstacle placement is well thought-out, and most levels have tendency towards being more or less maze-like, but with areas also flowing into each other in a smooth fashion.

For a very interesting contrast, consider the opening level of Wolfenstein 3-D with E1M1 of The Ultimate Doom. The former is very boxy and the flat maze-like feel is very prominent. Areas connect in a couple of hubs, with everything strongly separated by endless doors. The latter, however, isn’t just boxy corridors – rooms have distinctive shapes, depths, and heights, and they weave around each other. There are two main paths forward, one being obvious and the other secret, offering very different progressions towards their common endpoint, coming together again at the entrance to the semi-final room.

What both games do, however, is allow for choice. Contrast this with typical modern shooters, where indoor maps especially tend to be linear corridor-fests broken up by occasional scripted cutscenes or sequences. Exploration in that scenario doesn’t benefit progress; at best, it might give you a cute set-piece to look at. Doom’s idea of exploration, however, can bring you to all sorts of areas, many not required at all for the completion of the map, but existing anyway just to reward your curiosity; it might end in a fight, a weapon, a power-up, but something is going to be there.

While many modern shooters tend to have a pretty limited roster, Doom, in particular Doom II, has a total of 17 unique types of enemies covering a variety of roles and tiers, varying not just in simple shooting patterns, but having unique traits and capabilities. To list a few examples, Spectres blend with the shadows and tend to be used for flanking attacks, Cacodemons are capable of silent flight, Chaingunners are terrifyingly accurate snipers that provide constant covering fire for other enemies, Revenants have devastating punches and heat-seeking missiles, and Archviles can resurrect almost any monster in the game (even if they’re gibbed!).

Given all of these different sorts, the designers have a lot of possibilities to play with, and can create endless interesting and unique combat scenarios because of it.

Between the movement, weapons, items, level design, and enemies, Doom demonstrates many layers of depth that are enviable even today. Even after 28 years, people still can’t help themselves and endlessly remix levels, refine the gameplay, and use Doom’s engine and lessons as the basis for all-new creations. If not for the depth afforded (as well as generous GPL licensing), this would not be possible.

The BFG has two distinct firing phases. In the first, after a pause of about 8/10ths of a second, the giant green ball, the only visible projectile, is fired. While powerful on its own, the majority of the damage actually comes from the second stage. About half a second after impact, the BFG then fires 40 invisible tracers in a 45° angle from the player in the direction the player was facing the moment the gun was fired, but relative to their current position. The theoretical damage of the tracers against a single target is over 4 times that of the ball, though in practice it’s a good bit less due to the simplistic PRNG used. Note that these tracers are specifically not splash damage, as many assume; this makes it very viable against the two boss monsters, which are specifically immune to splash damage.↩︎